Focus: Mentorship training in LMICs needs increased support

January / February 2019 | Volume 18, Number 1

By Shana Potash

Whether helping young scientists shape their careers, conduct ethical research, or define a work-life balance, mentors are instrumental in nurturing future generations of global health researchers. But in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), formal mentoring is not often adequately supported by institutions or included in formal training programs. To encourage LMIC organizations to strengthen mentoring and institutionalize the practice, Fogarty Scholars and Fellows program faculty and alumni produced a new publication to serve as a guide.

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty

Mentorship training must be expanded and given more

institutional support in low- and middle-income countries,

according to a new publication by Fogarty-supported authors.

institutional support in low- and middle-income countries,

according to a new publication by Fogarty-supported authors.

Mentoring in Low- and Middle-Income Countries to Advance Global Health Research , a supplement to the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, offers recommendations, case studies and an overview of toolkits to help design mentorship programs tailored to LMICs. The publication was inspired by a series of “Mentoring the Mentor” workshops hosted in LMICs by faculty of Fogarty’s Global Health Program for Fellows and Scholars. It was edited by Dr. Craig Cohen, Co-director of the University of California Global Health Institute in San Francisco. More than 40 leaders in global health from around the world contributed to develop and publish the special issue.

“Great mentors are not born. Mentoring skills, like any other, must be developed,” Fogarty Director Dr. Roger I. Glass and Dr. Flora Katz, director of the Center’s extramural programs, note in the preface to the supplement. “It is our hope this collection of articles will provide a stimulus for increased funding to fill this critical need.”

- Related supplement article: Preface: Mentorship training is essential to advancing global health research , co-authored by Fogarty's Dr. Flora Katz and Dr. Roger I. Glass

Topics covered by the supplement include:

- Mentoring in the context of LMICs

- A framework for mentoring

- Evaluating mentorship programs

- Competencies for global health research mentoring

- Case studies for mentorship capacity development

- Addressing ethical issues through mentorship

- Mentoring toolkits

Mentoring in the context of LMICs

Formal mentoring is not yet common practice in many of the LMIC institutions that conduct global health research. However, a growing number of their scientists are interested in mentorship, and there is a strong need for it, according to supplement authors. They emphasize the importance of creating programs in the context of LMICs, considering the availability of resources and the culture within the institution and the country. “The advancement of global health research demands sustained career development opportunities for LMIC scientists that can only be attained via the implementation and dissemination of culturally compatible mentoring practices.”

While the existing guidance for successful mentoring is more in line with high-income settings, the authors describe how to adapt it, and address the challenges of implementing mentorship programs in LMICs. Institutions, for example, may not recognize or compensate faculty for their mentoring activities, making it financially unrewarding. Education approaches that reflect a country’s history or culture may be more authoritarian, hierarchal or paternalistic and could potentially deter junior scientists from disagreeing or bonding with their more senior mentor. And the male-dominated academic culture that is common among LMIC institutions can deter women scientists or limit their progress.

The authors recommend institutions formally acknowledge the value of mentoring by giving it a key academic role and providing protected time and compensation. To mediate the effects of a hierarchal culture, rules for respectful disagreement can be established to encourage critical thinking and make mentees comfortable expressing differences of opinion. Institutions should consider the age, gender, culture and other characteristics of faculty and students to support diversity. A work-life balance that would allow more opportunities for women or scientists with family responsibilities, for example, could increase the number and diversity of mentors. Other ways to cultivate quality mentors include joint training with scientists from high-income countries as well as group or peer mentoring.

- Related supplement article: Strengthening mentoring in low- and middle-income countries to advance global health research: An overview

A framework for mentoring

What is mentorship exactly? A frequently cited definition describes it as a process in which “an experienced, highly regarded person (the mentor) guides another individual (the mentee) in the development and re-examination of his or her own ideas, learning, personal and professional development.”

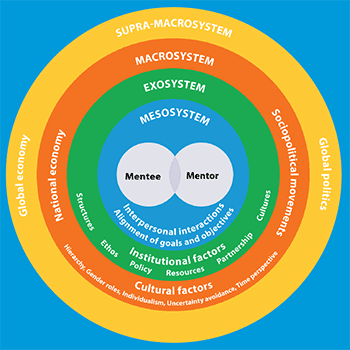

A Conceptual Framework for Mentoring

Systems of interaction between the mentor and mentee, visualized here,

are detailed in an article offering a conceptual framework for mentoring ,

published in a supplement to American Journal of Tropical Medicine

and Hygiene. Full description of the visualization below.

The relationship between mentor and mentee, according to supplement authors, should be mutually beneficial with each party learning from the other. This dynamic is central to a conceptual framework offered in the supplement to help mentors organize their work, generate new ideas and develop programs within their institutions. “One of the important factors that predicts success in this is the ‘click’ - the connection between the mentor and mentee,” the authors note.

Visualized as concentric circles, the framework highlights the mentor-mentee relationship and interactions that may affect it (see A Conceptual Framework for Mentoring graphic). Their bond, which may be influenced by age, gender and world view, is the center circle. The model expands next to institutional issues such as available resources and organizational ethos. Farther out are cultural and societal aspects including hierarchy and gender roles. Lastly are the global economy and politics, which may not have much effect on the mentor-mentee relationship, but may impact their work.

The framework also addresses mentee success and satisfaction - is their work a job, career, mission or calling? Here the authors distinguish between coaching, which is task-oriented, and mentoring which is person-oriented and can nudge the mentee toward a calling that brings high levels of satisfaction and success.

- Related supplement article: Conceptual framework of mentoring in low- and middle-income countries to advance global health

Evaluating mentorship programs

As mentorship is strengthened and more formal programs are developed and implemented, evaluation will be needed to determine best practices, plan mentoring activities, and demonstrate their value. To facilitate that, the supplement provides a framework identifying six areas for evaluation along with objective and subjective measures to assess them at the individual and institutional level. The latter is particularly important to LMIC institutions seeking to grow their mentoring capacity and optimize their resources, according to the authors.

- The mentor-mentee relationship can be assessed at the individual level by satisfaction surveys and by costs measured in time or money, for example, while evaluations by divisions, departments or schools can help identify gaps in institutional support.

- Evaluating career guidance at the individual level could be done by charting the progress of mentees and appointments or promotions for mentors. Their institutions may look at retention of prominent faculty and staff.

- Academic productivity for both parties at all levels could be viewed through published papers, invited talks or funded grants, but the authors suggest they be used alongside other categories as they may not fully reflect a mentor’s contributions.

- Networking, key to career development and global health research, can be evaluated at the individual level by describing the number of collaborators. Institutions can use bibliometric tools to analyze co-authorship, for example, and map the connections between investigators and institutions.

- Wellness, described as an innovation of the framework, reflects work-life balance and can be assessed individually with satisfaction surveys, and institutionally using validated tools that measure stress, lack of self-esteem and other factors that can lead to burnout.

- Organizational capacity creates the mentoring environment and could be measured by looking at the number of mentors and their age, gender and ethnic diversity, for example. Evidence of institutionalization, such as established training programs or promotions for mentors, could be monitored. Also important is self-perpetuation - to confirm that mentees are becoming mentors.

- Related supplement article: Evaluating academic mentorship programs in low- and middle-income country institutions: Proposed framework and metrics

Photo by David Snyder for Fogarty/NIH

High-quality mentorship can transform an LMIC scientist’s

career trajectory and shape the identity and success of

institutions, as noted in the supplement, published by the

American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

career trajectory and shape the identity and success of

institutions, as noted in the supplement, published by the

American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Competencies for global health research mentoring

Recognizing that high-quality mentorship can transform the trajectory of someone’s career and “shape the identity and success of institutions,” supplement authors identify nine core competencies for global health research. With north-south partnerships being at the heart of these initiatives, the authors say the proposed capabilities will help create more equitable relationships between investigators from high-income countries and LMICs.

Effective communication is paramount. Not only is it important to show empathy and compassion and to provide constructive feedback, mentors must be comfortable with cross-cultural and cross-gender communication. Because many LMIC academic institutions are dominated by men, the authors suggest special efforts be made to encourage the growth of female researchers and support them as role models and mentors to younger women.

Mentors must be able to help mentees align expectations with reasonable goals, assess a mentee’s talents, andprovide knowledge and skills needed to fill the gaps and achieve success. Addressing diversity is critical - mentors should embrace it by encouraging collaboration with all people and by recognizing their own biases, whether conscious or unconscious.

Fostering independence by demonstrating belief in a mentee, letting them take the lead, or assisting them in securing their own funding is key for mentoring, as is promoting professional development by guiding them as they work on a team, manage their time and develop communications skills. Mentors also must be able to promote professional integrity and ethical conduct by being a role model for it.

Mentors must have problem solving skills, patience in the face of adversity and other knowledge for overcoming resource limitations, given the LMIC environment. The final competency, fostering institutional change, is needed to advocate and negotiate for the development and implementation of mentoring programs.

- Related supplement article: Global health research mentoring competencies for individuals and institutions in low- and middle-income countries

Case studies for mentorship capacity development

To help LMIC institutions develop best practices for mentoring, the supplement contains several case studies.

When instances of plagiarism and cheating were discovered at Peru’s Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, the university used a Fogarty grant supplement to develop a free, online research integrity course. It includes a mentoring module with videos of university investigators discussing the role of mentors and their own experiences. The university and the Peruvian National Science and Technology Council both require completion of the course for anyone applying for a grant or registering as an investigator. Thousands of people have taken the online course and the concept of mentoring is now well recognized and valued, according to supplement authors.

A scientist aiming to strengthen mentoring at the Kenya Medical Research Institute used a Fogarty grant to assess mentoring at the Institute’s Centre for Microbiology. The assessment found universal interest from scientists, but only 40 percent had experience as a mentee and only 20 percent as a mentor. Barriers to the institutionalization of mentoring were identified, and a mentorship policy manual was drafted. Scientists are now working with U.S. colleagues to develop an institution-wide mentorship program.

With no formal mentoring program, “supervisor” and “guide” are the dedicated roles at India’s Saint John’s National Academy of Health Sciences and its affiliated research institute. Several efforts are being made to integrate mentorship into the culture. A new Vice Dean position was created to oversee postgraduate training and support improvements, including mentorship. Institution leaders sensitized staff to the difference between mentoring and supervision. In addition, young faculty have been participating in Fogarty’s Global Health Program for Fellows and Scholars, which gives them early exposure to mentoring.

In Mozambique, a mentorship program was established at the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. To maximize a limited pool of mentors, monthly group meetings for interested researchers, ranging from undergraduate to Ph.D. students, were initiated. Since these meetings began, more faculty and junior researchers have become interested in mentorship, mentees have found a support system in their peer group, and more mentees are prepared to mentor the next generation of students.

There are several key takeaways from the case studies, as noted by the authors. Developing a free, online course for responsible conduct of research that includes mentoring, and having it endorsed by the most significant research sponsor in the country, are best practices that could be replicated. Needs assessments can identify gaps and help strengthen mentoring. While institutional support is critical, group or peer mentoring can be effective when resources are limited. The authors note that collaborations between LMIC institutions and those in high-income countries - and efforts such as the “Mentoring the Mentor” workshops and the Fogarty Global Health Fellows and Scholars program - can serve as catalysts to strengthen mentoring.

- Related supplement article: The evolution of mentorship capacity development in low- and middle-income countries: Case studies from Peru, Kenya, India, and Mozambique

- Related supplement article: Mentoring the mentors: Implementation and evaluation of four Fogarty-sponsored mentoring training workshops in low-and middle-income countries

Addressing ethical issues through mentorship

Mentors play a critical role in ensuring scientific integrity by addressing the responsible conduct of research and serving as a model for it. Through literature review, supplement authors identified and provided suggestions to avoid misconduct in four areas: preventing plagiarism, determining valid authorship, the appropriate use of IRBs and considering imbalances of power.

To reduce plagiarism, the authors suggest online programs that check for it, promoting scientific writing courses, including modules on plagiarism in responsible conduct of research courses, and holding one-on-one discussions about it when editing a mentee’s work.

Fairness and integrity should be the guiding principles in determining authorship of a publication. From the initial design of a study through the analysis and writing phases, mentors can offer guidance on the criteria for authorship, the appropriate order, and how to handle guest and ghost authors.

Mentors need to be well-informed about the latest local and international regulations governing biomedical research. Potential violations of IRB and Ethics Review Committee approval include changes in an approved study location, type of sample needed for research procedures, wording used for participant consent or amount of participant compensation.

Noting that a researcher’s primary ethical obligation in global health is to “improve the health and well-being of the individuals and communities they visit,” the authors say mentors must teach the importance of empowering local investigators.

- Related supplement article: Mentorship and ethics in global health: Fostering scientific integrity and responsible conduct of research

Mentoring toolkits

Mentoring Toolkit Review

These 18 existing global health mentoring toolkits were reviewed. Access links to each of the toolkits in Table 1 of the supplement article, Global Health Mentoring Toolkits: A Scoping Review Relevant for Low- and Middle-Income Country Institutions .

- Mentoring Handbook

The Afya Bora Fellowship in Global Health Leadership - Fogarty Fellows Toolkit for Mentorship

Fogarty Global Health Fellows and Scholars consortium - Morehouse School of Medicine: Mentoring Academy

Morehouse School of Medicine - Faculty Mentoring

Stanford University School of Medicine - Mentorship Guidelines for Global Health Mentors

University of California, San Francisco - Guidelines for mentor/mentee conversations

Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania - Mentoring Program Virtual Binder

Center for AIDS Research, University of California, San Francisco - University of Washington Mentoring Resources

University of Washington - Preparing for International Health Experiences: A Practical Guide

edited by Akshaya Neil Arya - American Heart Association Mentoring Handbook

American Heart Association - CCGHR-Mentoring Modules

Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research - CUGH Field Experience Checklist

Consortium of Universities for Global Health - Faculty Preparation for Global Experiences Toolkit

National League for Nursing - Getting the Most out of Your Mentoring Relationship

available for Association for Women in Science members - Mentoring and Being Mentored

American Physiological Society - I-TECH Clinical Mentorship

I-TECH - Nature’s guide for mentors

Nature - Medical Student Mentoring Guide

American Association of Medical Colleges

One way to strengthen mentorship is through toolkits - written or online resources that offer guidance to mentors, mentees and institutions. But material written specifically for LMICs is scarce.

In the supplement’s final article, researchers reviewed existing mentoring toolkits - focusing on those developed by organizations involved in global health mentoring, written in English, and containing any guidelines that could be applied to LMICs.

Authors identified and summarized 18 toolkits - providing a brief description, the intended audience, competencies addressed, tools included and other helpful information, along with weblinks to access the resource.

With this series of articles, the team of authors aims “to help herald in a new era of increased mentoring in LMICs that leads to advancement of global health research and practice around.”

- Related supplement article: Global health mentoring toolkits: A scoping review relevant for low- and middle-income country institutions

More Information

- Mentoring in low- and middle-income countries to advance global health research [Open access]

The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, January 2019 - Preface: Mentorship training is essential to advancing global health research

- Strengthening mentoring in low- and middle-income countries to advance global health research: An overview

- Conceptual framework of mentoring in low- and middle-income countries to advance global health

- Global health research mentoring competencies for individuals and institutions in low- and middle-income countries

- Mentoring the mentors: Implementation and evaluation of four Fogarty-sponsored mentoring training workshops in low-and middle-income countries

- The evolution of mentorship capacity development in low- and middle-income countries: Case studies from Peru, Kenya, India, and Mozambique

- Evaluating academic mentorship programs in low- and middle-income country institutions: Proposed framework and metrics

- Mentorship and ethics in global health: Fostering scientific integrity and responsible conduct of research

- Global health mentoring toolkits: A scoping review relevant for low- and middle-income country institutions

Description of conceptual framework for mentoring visualization: Four concentric circles show the systems of interaction between the mentor and mentee.

- First circle (at center): Mesosystem. Interpersonal interactions. Alignment of goals and objectives. Contains mentee and mentor.

- Second circle: Exosystem. Institutional factors: Structures, Ethos, Policy, Resources, Partnership, Cultures.

- Third circle: Macrosystem. Sociopolitical movements. Cultural factors: Hierarchy, Gender roles, Individualism, Uncertainty avoidance, Time perspective. National economy.

- Fourth (outer) circle: Supra-macrosystem: Global politics, Global economy.

To view Adobe PDF files, download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website .

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario