Multigenerational research leads to HIV discoveries

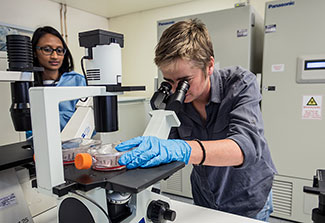

Photo by Aga Szydlik of the National Institute for Communicable

Diseases and the University of the Witwatersrand

Several generations of Fogarty trainees in South Africa have

helped advance HIV prevention research with their work on

broadly neutralizing antibodies, including Dr. Penny Moore

(center) and her mentee Dr. Jinal Bhiman.

helped advance HIV prevention research with their work on

broadly neutralizing antibodies, including Dr. Penny Moore

(center) and her mentee Dr. Jinal Bhiman.

Three generations of Fogarty-trained scientists in South Africa have made notable contributions to an area of research that might yield new ways to prevent HIV. They're studying broadly neutralizing antibodies, which can kill multiple strains of the virus that causes AIDS. Produced by only about 20 percent of people with HIV, these antibodies show up too late to be able to stop disease progression in the people who make them. However, scientists worldwide are exploring their potential to prevent HIV in others - either through a vaccine that would coax the body to generate similar types of antibodies or via passive immunization in which an antibody product would be given directly.

In work that's spanned more than a decade and passed from mentors to mentees, the South African team and U.S. collaborators have helped explain how these unusual antibodies can arise. More significantly, they discovered and isolated an especially potent antibody that was shown to protect monkeys from infection. The antibody is being modified and mass produced for a future trial to determine if it can safely and effectively do the same in people.

"This is a rolling stone that's gathering a lot of moss along the way and generating a whole slew of really exciting young scientists," said Dr. Salim Abdool Karim, director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) , who is planning the trial.

For 25 years, Fogarty support has provided long- and short-term training to hundreds of South African scientists and helped build the capacity required to run successful research labs and conduct clinical trials there. As the trainees become the trainers, Abdool Karim said the multiplier effect is tremendous and cited as a good example the antibody research conducted by Dr. Lynn Morris, her mentee Dr. Penny Moore, and her trainee Dr. Jinal Bhiman.

The road to discovery

Three generations of Fogarty research trainees

Photos by Aga Szydlik/University of Witwatersrand

Morris and Moore, CAPRISA research associates, co-direct the antibody program at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg. Their lab brings together the fields of virology and immunology and conducts studies to understand how and why some people develop broadly neutralizing antibodies, which can take two to four years to reach their peak HIV-fighting form.

Much of their antibody research centers on samples collected over years from women in a large CAPRISA study who were diagnosed with HIV within weeks of infection. Serum samples, collected years later from these women, were tested against panels of HIV strains, to allow the research team to identify those women who had developed broadly neutralizing antibodies. Then, by going back to stored specimens, the researchers were able to study how those antibodies and the virus changed over time. This unique cohort, which began in 2004, therefore gives the scientists the opportunity to study both the virus and the antibodies from their earliest stages and trace their evolutionary pathways.

These relatively rare antibodies have been discovered in the samples of several women, but one participant, known as CAP256, was found to have especially potent plasma antibodies. For the skills and technologies to isolate the B cells that make these antibodies, Morris turned to Fogarty training for herself and later Bhiman, who finished the task with the help of collaborators at NIH's Vaccine Research Center.

The Fogarty factor

Morris said the Fogarty training she received early in her career in 1999 started a trend of collaborations between her lab and international partners, which has created valuable learning opportunities for their students. "It's really had the most significant impact in terms of getting our trainees to another level because they come back with all these new skills and with that comes more confidence."

It's also enabled their team to keep up with the latest technologies. Morris went for additional Fogarty-supported training in 2009, spending time at Duke University, to learn how to isolate the individual blood cells that produce broadly neutralizing antibodies - work compared to finding a needle in a haystack. She pulled out antibodies from the blood of two CAPRISA patients, but not CAP256, because at that time they didn't have the right antigen, or "bait." Morris brought the B cell technology from that experience back to South Africa and along with another trainee, Dr. Nono Mkhize, set it up in their lab. They still use it today for CAPRISA projects and to support NIH-funded vaccine trials in the country.

When Moore joined the lab as a postdoctoral fellow unsure of the direction she wanted her career to take, Morris suggested she spend time with Dr. James Binley at the Torrey Pines Institute in San Diego, who was studying HIV envelope structures and how antibodies bind to them.

"It was a completely transformative experience for me," said Moore, of the two rounds of training she had there in 2004 and 2006. Moore said she came home “addicted" to the work. It's been her research focus ever since, and an interest she cultivated in Bhiman as she completed her master's and Ph.D. Moore included Bhiman in research that resulted in a significant paper published in 2012, which was the first to show, in concept, that viral evolution directs the antibody response. Scientists have long known that antibodies pressure the virus to change; the South African team showed the opposite is also true.

When Bhiman began work on her Ph.D., Moore and Morris decided it was time to make another attempt at isolating the CAP256 antibodies and turned to their collaborators at NIH's Vaccine Research Center. In 2012 and 2014, Bhiman trained there alongside scientists who are pioneers in this area, and learned two different techniques for isolating the B cells that produce these unusual antibodies. Mentored by VRC Director Dr. John Mascola and Drs. Nicole Doria-Rose and Nancy Longo, Bhiman executed the time-consuming work of finding these very rare cells in a vial of blood cells.

They ultimately isolated 33 antibodies from CAP256, including the exceptionally potent one that's heading to trial. Without this step, researchers wouldn't have been able to clone the antibody and produce it in large enough quantities for animal and human studies.

Image courtesy ofJinal Bhiman (PDB ID: 4OD1)

Former Fogarty trainees and collaborators at

NIH's Vaccine Research Center isolated an

exceptionally potent antibody, known as

CAP256-VRC26.25, that is being developed

for a future trial to determine if it can protect

people from HIV infection.

NIH's Vaccine Research Center isolated an

exceptionally potent antibody, known as

CAP256-VRC26.25, that is being developed

for a future trial to determine if it can protect

people from HIV infection.

This collaborative effort between the VRC and South African researchers also produced findings with implications for vaccine development. Scientists showed that these antibodies were born with, rather than developed, the unusually long arms that enable them to penetrate the protective coating of HIV and neutralize it. That work was published in 2014. The following year, Bhiman was lead author on a study that delineated the viral events that caused the antibodies to mature from being strain-specific to broadly neutralizing.

"I feel very privileged and very lucky to have been given the opportunity to work on the CAP256 project," noted Bhiman, who's now a postdoc at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego. Her time at the NIH and her mentors there gave her a very different view of science compared to that in the developing world. And her years with Morris and Moore built her confidence as a researcher. "The benefits of my Fogarty training have extended well past the training time," she said.

Mentoring matters

Bhiman was one of nearly a dozen students mentored by Morris and Moore who spent time training in top U.S. labs with Fogarty support. The students were carefully selected once they'd developed some lab skills and had a clearly defined research question. They were then sent to learn from collaborators who were the best match for that specific project. For those reasons, Morris said, they were all very successful.

Moore observed that the trainees return with a new perspective. "I think what it really brings is exposure - if you can get exposure to a really top lab, it gives you an idea of the energy, money and the technologies," she said. "I think that can change the way you view the science you are doing."

The Fogarty experience has led to a "cascade of capacity building," spawning an array of new projects, new collaborations and new grants, Moore noted. But, it also created what she described as a nurturing network. "It becomes a much bigger thing than just the scientific techniques that people went off to a lab in the U.S. to learn. It becomes a community." Their lab has become highly collaborative and formed useful networks, according to Morris. "The Fogarty training programs have been the major mechanism for doing that, which has been really fantastic for building our expertise."

For many of the trainees, it was a seminal experience. "It was career-defining for many of us because it gave us opportunities I don't think we would have had anywhere else," said Moore. "I really can't overstate the value of the Fogarty programs for us. It's changed the way we do science; the way we interact with other labs and it's increased the opportunities open to our students."

Adapted from the January / February 2018 Global Health Matters article Multigenerational research in South Africa leads to HIV discoveries.

More Information

- Recorded webcast of the related presentation by Dr. Salim Abdool Karim:

The global benefits of building AIDS research capacity in South Africa: The case of HIV prevention in women [Video]

International AIDS Society (IAS) conference, July 25, 2017 - Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA)

- National Institute for Communicable Diseases , South Africa

- NIH Vaccine Research Center (VRC) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

- Related publications:

- Evolution of an HIV glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibody epitope through immune escape

Nature Medicine, October 21, 2012 - Developmental pathway for potent VIV2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies

Nature, May 1, 2014 - Viral variants that initiate and drive maturation of V1V2-directed HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies

Nature Medicine, October 12, 2015 - New member of the V1V2-directed CAP256-VRC26 lineage that shows increased breadth and exceptional potency

Journal of Virology, December 17, 2015 - NIH news and information on broadly neutralizing antibodies:

- NIH launches large clinical trials of antibody-based HIV prevention

NIAID/NIH news, April 7, 2016 - Study of antibody evolution charts course toward HIV vaccine

NIAID/NIH news, March 3, 2014

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario