Cost-Effectiveness of Community-Based Tobacco Dependence Treatment Interventions: Initial Findings of a Systematic Review

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW — Volume 16 — December 12, 2019

Sarah A. Reisinger, PhD, MPH, MCHES, TTS1,2; Sahar Kamel, MBChB, MS, TTS2; Eric Seiber, PhD3; Elizabeth G. Klein, PhD, MPH1; Electra D. Paskett, PhD, MSPH2,4,5; Mary Ellen Wewers, PhD, MPH1 (View author affiliations)

Suggested citation for this article: Reisinger SA, Kamel S, Seiber E, Klein EG, Paskett ED, Wewers ME. Cost-Effectiveness of Community-Based Tobacco Dependence Treatment Interventions: Initial Findings of a Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:190232. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.190232.

PEER REVIEWED

On This Page

Summary

What is already known on this topic?

Tobacco use poses a substantial economic burden on society, yet community-based interventions continue to be overlooked. Studies have shown tobacco dependence treatments, ranging from brief clinician advice to specialist-delivered intensive programs, are highly cost-effective.

What is added by this report?

This review addresses a gap in the scientific literature and demonstrates that community-based tobacco dependence treatments are cost-effective.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The low costs per quit and low incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of community-based programs indicate that these programs are a valuable component of comprehensive tobacco control. Efforts should continue to promote such programs.

Abstract

Introduction

Scientific literature evaluating the cost-effectiveness of tobacco dependence treatment programs delivered in community-based settings is scant, which limits evidence-based tobacco control decisions. The aim of this review was to systematically assess the cost-effectiveness and quality of the economic evaluations of community-based tobacco dependence treatment interventions conducted as randomized controlled trials in the United States.

Methods

We searched 8 electronic databases and gray literature from their beginning to February 2018. Inclusion criteria were economic evaluations of community-based tobacco dependence treatments conducted as randomized controlled trials in the United States. Two independent researchers extracted data on study design and outcomes. Study quality was assessed by using Drummond and Jefferson’s economic evaluations checklist. Nine of 3,840 publications were eligible for inclusion. Heterogeneity precluded formal meta-analyses. We synthesized a qualitative narrative of outcomes.

Results

All 9 studies used cost-effectiveness analysis and a payer/provider/program perspective, but several study components, such as abstinence measures, were heterogeneous. Study participants were predominantly English speaking, middle aged, white, motivated to quit, and highly nicotine dependent. Overall, the economic evaluations met most of Drummond and Jefferson’s recommendations; however, some studies provided limited details. All studies had a cost per quit at or below $2,040 or an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) at or below $3,781. When we considered biochemical verification, sensitivity analysis, and subgroups, the costs per quit were less than $2,050 or the ICERs were less than $6,800.

Conclusion

All community-based interventions included in this review were cost-effective. When economic evaluation results are extrapolated to future savings, the low cost per quit or ICER indicates that the cost-effectiveness of community-based tobacco dependence treatments is similar to the cost-effectiveness of clinic-based programs and that community-based interventions are a valuable approach to tobacco control. Additional research that more fully characterizes the cost-effectiveness of community-based tobacco dependence treatments is needed to inform future decisions in tobacco control policy.

Introduction

In the United States, tobacco use, the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality (1), poses a substantial economic burden. Nationwide, smoking causes an estimated $332 billion in annual lost productivity and direct health care costs (1,2). Elimination of combustible tobacco use will dramatically reduce this burden (1).

Community-based cessation approaches, such as quitlines, internet, and self-help interventions, are important components of comprehensive tobacco control. Although community-based initiatives may have lower cessation rates (3) than clinic-based programs, they are effective as they engage more participants than do clinic-based programs, including underserved and hard-to-reach smokers (4–6). Because community-based interventions are often less expensive to deliver, they may be as cost-effective as clinic-based interventions. Furthermore, community-based programs offer an opportunity for tailored behavioral interventions to facilitate optimal outcomes and reduce tobacco use disparities (7).

Cessation interventions can immediately affect the economic and public health consequences of tobacco use (8). Yet comprehensive tobacco control efforts, which are typically organized at the state level and include administrative, surveillance, evaluation, and monitoring components, incur high implementation costs. These costs are allocated toward changing social norms, increasing cessation, and reducing exposure to secondhand smoke. It is essential that decision makers have tools such as economic evaluation to make informed decisions about how to allocate resources.

Few economic evaluations of controlled community-based trials in the United States have been published, and no comprehensive literature review exists. This void limits evidence-based decision making and resource allocation and negatively affects health outcomes. This review addresses the void by systematically assessing the cost-effectiveness and quality of economic evaluations of community-based tobacco dependence treatments conducted as randomized controlled trials in the United States. This report potentially informs tobacco control policy, contributes to population-level strategies, and improves future economic evaluations by illustrating best and current practices.

Methods

We searched 8 databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry, EMBASE, CINHAL, Scopus, Web of Science, Global Health, and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database) by using medical subject headings and synonyms for tobacco dependence treatment, economic evaluation, and randomized controlled trial. We searched databases from their beginning to February 2018.

Study selection

Selection criteria were structured by population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (Box). We included economic evaluations that randomized individuals or communities to intervention or control groups. We excluded review articles but examined them for studies that met criteria. All outcome time points, perspectives (ie, societal, payer/provider/program, or individual), and types of economic evaluations were included. We also included studies without biochemical verification. Our review focused on community-based tobacco dependence treatments, such as those delivered through quitlines/telephone counseling, in-person counseling, postal mail, and the internet, and included alternatives to traditional, medically trained clinical interventions. Although “community-based” has several definitions, we defined it as programs that 1) referred to a community as a setting or a geographic location where interventions were implemented, 2) included a variety of approaches, levels, and locations, and 3) focused on changing individuals’ behavior as a method of reducing population risk (9). Locations included state quitlines and local and population-based residents throughout the United States (reached by postal mail, internet, telephone counseling, and in-person counseling). Only studies with adult smokers and abstinence-framed measures such as cost per quit and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (ie, attributable cost per quit) were included. We excluded special or targeted populations such as adolescents, employees, insured, and hospitalized patients; studies conducted outside of the United States; and studies solely reporting outcomes in terms of enrollees, patients, or recruitment.

Box. Selection Criteria Structured by Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, and Study Design (PICOS)

| Element | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult smokers; United States; community-based (accessible to broader populations, including socioeconomically disadvantaged populations) | Adolescents, worksite/employees, clinics, hospitals/inpatients, pregnant women, former smokers, insured, groups with specific conditions (eg, cancer patients, substance abuse), non-US setting |

| Intervention | Tobacco dependence treatment; smoking cessation (includes quitline) | — |

| Comparator | Controls, usual care (includes quitline) | — |

| Outcome | Abstinence-framed outcomes, such as but not limited to cost per quit, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, quality-adjusted life year | Outcomes framed only as patient, enrollee, or recruitment |

| Study design | Controlled trials with economic evaluation, which randomized individuals or communities to an intervention or control condition | Observational studies, studies that did not randomize individuals or communities to an intervention or control condition, studies without economic evaluation |

The search strategy was reviewed by an academic research librarian. To avoid publication bias, we performed gray literature searches of ClinicalTrials.gov, conference reports and proceedings (The Conference Board and Conference Proceedings Citation Index), and dissertations (WorldCatDissertations and Theses) to include reports, book chapters, conference abstracts, and dissertation theses. To avoid language bias, we included all languages. All publications indexed were included without date restrictions.

We removed duplicates, and 2 researchers (S.A.R., S.K.) independently performed an initial screening of titles and abstracts. Publications remaining were reviewed in entirety to determine eligibility. References in included studies were reviewed. We contacted authors for additional information when necessary. The same 2 researchers independently abstracted data and assessed quality. Any disagreement or uncertainty was resolved through discussion or a third independent researcher (M.E.W.).

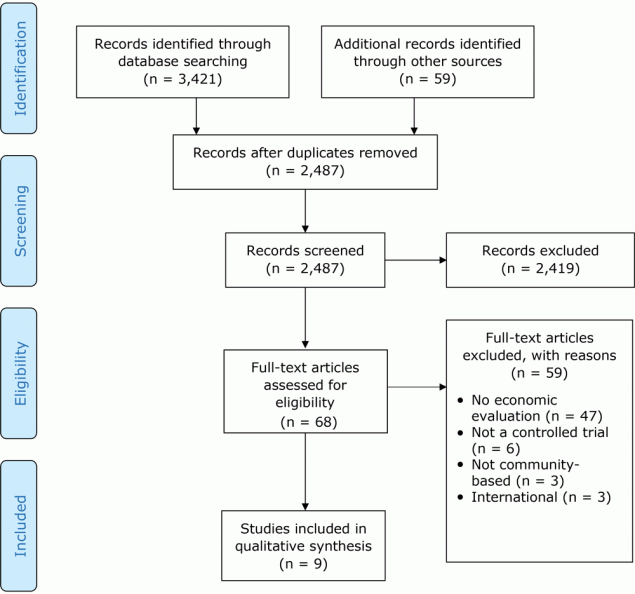

Initial searches returned 3,480 articles. After removing 993 duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts of 2,487 records. Of these, 2,419 were excluded, leaving 68 full-text articles that were systematically examined for the following criteria in the following order: presence of an economic evaluation, randomized controlled trial, community-based, and set in the United States. Of these 68 studies, 9 that were published in peer-reviewed journals met inclusion criteria (Figure).

Figure.

Article search and selection process using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). “Records screened” are titles and abstracts. [A text version of this figure is also available.]

Data extraction

Two researchers (S.A.R., S.K.) independently abstracted data for 1) research question, objective, or hypothesis, 2) location or setting, 3) population description, 4) study design and intervention description, 5) intention-to-treat analyses, 6) summary effects, 7) type of economic evaluation, 8) perspective, 9) the analytic horizon, or the duration of the study time frame including outcome assessment (22), 10) type of abstinence measure used for the economic evaluation, 11) source of the valuation of resources (eg, invoices, contracts, website data) used to determine costs, or how components of intervention were valued, 12) sensitivity analyses, 13) economic evaluation results, 14) subgroup analyses, 15) generalizability, and 16) limitations. We assessed the quality of each study by using Drummond and Jefferson’s economic evaluation checklist (10), which consists of 35 questions that use 4 response options (yes, no, not clear, and not appropriate) to assess study design, sources and quality of data collected, data analysis, and interpretation of results. We noted any items not explicitly addressed but inferred from the text. We synthesized a qualitative narrative of outcomes. We assessed inter-rater reliability by calculating percentage agreement, expected agreement, and the Cohen κ statistic in Stata version 12 (StataCorp LLC). Cohen κ, values for which range from −1 to +1, represents the proportion of agreement after chance is excluded; larger values indicate better reliability. The statistic accounts for the possibility of guessing, but the assumptions of rater independence and other factors may lower the estimate of agreement, and interpretation and accepted values can vary by discipline (11,12).

Results

For the initial review of titles and abstracts, the agreement rate was 98.6%, the expected agreement was 94.3%, and Cohen κ was 0.75. The agreement for full article review was 91.2%, the expected agreement was 72.7%, and Cohen κ was 0.68. The agreement for reasons of exclusion was 92.6%, the expected agreement was 76.3%, and Cohen κ was 0.69. The agreement for quality assessment was 93.9%, the expected agreement was 31.0%, and Cohen κ was 0.91.

Study setting and implementation. The primary setting for the 9 studies was quitline or telephone counseling (13–18). Other settings included in-person counseling (19), postal mail (17,20,21), and internet (14). Quitlines and telephone counseling were located in New York (18), Wisconsin (15), Oregon (16), Colorado (13), National Jewish Health (Denver, Colorado) (14), and the American Cancer Society in Texas (17). Studies were initiated over a wide time frame (1979–2010); 8 studies began in 2000 or later. Publication dates ranged from 1984 to 2016.

Interventions. Interventions tested the effect of type (15,18) and/or duration (13,15,16,19) of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), duration and intensity of mailed self-help (20,21), quitline and self-help (17), and basic internet, enhanced internet, and enhanced internet plus telephone counseling (14) (Table 1).

Study populations. Study populations varied; generally, participants were English-speaking, middle aged, white, motivated to quit, and highly nicotine dependent. Key factors that differed were number of cigarettes consumed or level of nicotine dependence, smoking history, interest or willingness to receive or use NRT, willingness to quit smoking, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Measures of abstinence. All studies provided details about how treatment effectiveness was defined and measured. The most commonly used definitions of abstinence for the economic evaluation were self-reported 7-day point prevalence (15,18–20) and 30-day point prevalence (13,14,16,21). Other definitions included multiple point prevalence (14), continuous abstinence (21), and maintained cessation with no more than 5 single-day slips (brief relapses or resumption of smoking for the delineated period of time) in a 3-month interval (17). The most common time points were 6 months (13–16,19) and 12 months (14,17,21). Other time points included 3 months (14), 7 months (18), 18 months (14), and 24 months (20). All studies addressed intention-to-treat analysis, in which nonrespondents were classified as smokers. However, 2 studies used intention-to-treat analyses in slightly different ways (16,18). Most studies defined abstinence on self-reported data (13–16,18,20,21), but 2 used biochemical verification to varying degrees (17,19). Seven studies (13,18) demonstrated a significant treatment effect (ie, difference in abstinence).

Perspective. Three studies explicitly stated the perspective (14,16,20). Among the remaining studies, perspective could be inferred (13,15,17–19,21). All studies used the payer/provider/program perspective; 1 study examined costs incurred by participants (ie, an individual perspective), but this approach was excluded in the original study’s final analyses (19).

Costs. Overall, studies provided various levels of detail on costs (Table 2). Four studies indicated the resource that was used to determine how the component was valued (ie, source of the valuation) (13,14,19,21). When reported, information on costs was typically obtained from prevailing commercial costs, economies of scale, or study records. Most studies reported aggregate data with various levels of detail about which intervention components were included.

Analytic horizon. The analytic horizon was explicitly addressed by 1 study (14) and easily understood in all other studies. Horizons varied from 3 to 24 months; most were 6 or 7 months (13–16,18), and one was a single 24-month follow-up study (20). One study had multiple periods of assessment (3, 6, 12, and 18 months) (14).

Discounting. Discounting was not performed in any of the studies but was discussed in one (14).

Sensitivity analyses. Many studies provided sufficient details of statistical tests and confidence intervals (13–20). Some degree of sensitivity analysis or uncertainty analysis was performed in relation to the economic evaluation in 5 studies (14,16,18,19,21); no study varied costs. Two studies used 95% confidence intervals (18,19), two used varied abstinence measures (14,21), and one examined the effect of using responder-only data in lieu of intention-to-treat data (16).

Cost-effectiveness. All studies conducted cost-effectiveness analyses, used cost per quit and/or ICER to present findings, and answered the study question posed. The combination of cost per quit and ICER was commonly used (14–16,18). Two studies calculated cost per quit only (13,21) and 3 studies reported ICER only (17,19,20). Studies compared relevant alternatives with various levels of detail (13–16,18–21). Data and results were typically presented in disaggregated and aggregated form to allow readers to calculate other ratios (14–21). Conclusions were provided for all but 1 study (17).

Despite various abstinence definitions, assessment time points, and scale of tobacco dependence treatments, the cost-effectiveness estimates were relatively similar (Table 3). Overall, when combining all studies, despite settings and methodology differences, cost per quit ranged from $5 (14) to $2,040 (16) and the ICER or cost per additional quit ranged from $357 (15) to $3,781 (14). When considering sensitivity analyses and the use of biochemically verified data, the ICER increased to $6,781 (19).

Cost per quit. When comparing combination therapy to monotherapy and duration of NRT therapy, using actual estimates only (excluding subgroup and sensitivity analyses), cost per quit ranged from $102.44 (18) (2 weeks of patch only) to $675 (15) (6 weeks of combination therapy). In studies examining duration of patch-only interventions, cost per quit ranged from $883 (4 weeks) (13) to $2,040 (8 weeks) (16). When examining dose or intensity of self-help interventions, cost per quit ranged from $5 for basic internet to $1,882 for enhanced internet plus phone (14). Conditions such as enhanced internet (14), mailed leaflets, leaflets plus maintenance manual, cessation manual, and cessation manual plus maintenance manual (21) were comparable.

ICER. Similar to cost per quit, when comparing combination therapy, monotherapy, and duration of NRT therapy, using actual estimates only, the ICER ranged from $357 (15) (2 weeks of combination therapy) to $3,131 (16) (8 weeks of patch only). When considering sensitivity analyses and the use of biochemically verified data, the range increased to $6,781 (19). When examining dose or intensity of self-help interventions, the ICER ranged from $361 (20) (intensive repeated mailings) to $3,781 (14) (enhanced internet plus phone). Compared with mailed self-help booklets alone, the cost per additional quit attributable to telephone counseling availability was approximately $1,300 (17).

Subgroup analysis. Three studies included subgroup analyses in the economic evaluation, including a comparison of combination therapy and monotherapy among uninsured participants (18), differences in abstinence by intervention use (14), and the effect of requesting 2 NRT shipments (13).

Generalizability. Two studies reported that the study design translated to real world or national samples (15,20). One study noted uncertainty about whether the sample would generalize to other smokers (14); others indicated the eligibility criteria (13,19) or intervention type (21) might limit the representativeness.

Quality. The quality of the economic evaluations varied; generally, studies addressed most recommended items (Table 4) (10). Either explicitly or implied, 1 study addressed all 35 items in Drummond and Jefferson’s economic evaluations checklist (14), 6 studies described 89% to 97% of applicable items (15,16,18–21), and 2 studies reported on 80% of applicable items (13,17). Many topics, such as research question, viewpoint, costing, currency, time horizon, discounting, and sensitivity analysis, were implied. Although Drummond and Jefferson’s recommendations do not specify reporting of financial support, 8 studies reported federal (14,15,18–20), state (13,16–18), institutional (20), or industry (13) support.

Discussion

Our review systematically assessed the cost-effectiveness and quality of the economic evaluations of community-based tobacco dependence treatment interventions conducted as randomized controlled trials in the United States. The studies reviewed addressed most of Drummond and Jefferson’s recommendations for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions; however, some studies provided limited details. Based on cost-effectiveness estimates reported among studies of predominantly middle-aged, white, motivated to quit, and highly nicotine dependent populations, basic internet had the lowest cost-effectiveness ratio. However, all interventions, even when considering biochemical verification, sensitivity analysis, and subgroup analysis, had a cost per quit of less than $2,050 or an ICER of less than $6,800. Thus, considering the most commonly accepted conservative threshold of $50,000 per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY), all community-based interventions were cost-effective.

According to Drummond and Jefferson, cost-effectiveness comparisons among health care interventions should be made only when methods and settings are closely aligned (10). In our review, no studies used QALYs or a similar outcome, which would have allowed for direct comparison with studies on other health conditions. However, the cost-effectiveness estimates of community-based interventions in our review (ie, cost per quit or ICER at or below $2,040 or $3,781, respectively) were similar to estimates in studies of clinical settings (ie, a few hundred to a few thousand dollars per quit [23–29]). Although community-based tobacco dependence treatment cost-effectiveness estimates in our review align with previous clinical findings and findings of nonrandomized controlled studies, more research is needed before definitive comparisons can be made.

Treatment for tobacco use is considered the gold standard of health care cost-effectiveness (30). Ranging from brief clinician advice to specialist-delivered intensive programs, including NRT or other medications, such treatment has been shown to be highly cost-effective (23). Population-wide policy, systems, and environmental changes, such as increases in the unit price of tobacco products, comprehensive smoke-free policies, and media campaigns increase cessation rates by motivating users to quit, increasing demand for tobacco dependence treatment, and making it easier to quit (7,8,31–33). These approaches are most efficient and effective at reaching many people (7,31,33); however, policies and media campaigns require substantial resources, and like clinical interventions, they are often not tailored to specific populations in need, do little to directly address disparities in tobacco use and tobacco-attributable health outcomes, and fail to engage hard-to-reach populations, such as those with social, economic, or geographic constraints.

In contrast, community-based programs are frequently tailored to targeted audiences. Tailored programs and messages are more effective than standardized, nontailored interventions (34), and have a greater effect on health behavior because they are often perceived as more relevant than generic communication (35–37). These benefits in reach and efficacy, which occur largely through engagement in evidence-based community interventions, can help reduce disparities in tobacco use (7). Furthermore, community-based programs, such as those using community health workers, have strong potential for improving health outcomes (38). Although clinical and policy-based approaches are important, they are also labor intensive, costly, and do little to address subgroups of populations who are underserved. Community-based interventions are poised to focus on those gaps. This review shows community-based tobacco dependence treatment approaches are both effective and cost-effective and an important component of comprehensive tobacco control. With this additional information on the cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions, efforts should continue to promote such strategies.

Our study has several strengths. The systematic review used a comprehensive search strategy that was informed and reviewed by an academic research librarian. We used 2 independent researchers and a third to resolve conflicts with high interrater agreement. The search was performed in 8 databases and gray literature, which produced substantial overlap in returned results. The quality assessment used Drummond and Jefferson’s established criteria and checklist, which is recommended in Cochrane reviews to inform appraisal of the methodological quality of economic evaluations (39). The study was limited in scope to include economic evaluations of community-based studies of tobacco dependence interventions conducted as randomized controlled trials in the United States. We identified a considerable number of studies outside the United States, but differences across countries’ cost structures and health systems would have limited the validity of our review (10). Randomized controlled clinical trials were selected as the gold standard for estimating efficacy of treatment interventions and greatest internal validity.

Our study has several limitations. We excluded several target populations (ie, adolescents, employees, insured, and patients) and other settings (ie, clinical settings and worksites) to increase the reliability of the findings. The only groups included a priori were low-resource groups, such as the uninsured. Socioeconomically disadvantaged populations underutilize smoking cessation treatments and are studied infrequently. Although some groups (eg, mentally ill, people who use drugs) could potentially be classified as low-resource, we determined that the underlying conditions would further complicate generalization. A broad body of research on those groups could be reviewed separately.

Cost-effectiveness ranges in our review were generalities; the ranges were not adjusted, because we lacked dollar-year data. However, when we used presumed dollar-years, adjusted cost-effectiveness estimates for the oldest study (21) and the study with the highest reported cost per quit (16) were below $2,700 in 2019 dollars. These approximations demonstrate that our findings would retain low cost-effectiveness ratios if dollar-year data were available to adjust costs to a single referent year. We could not directly compare the cost-effectiveness estimates among the 9 studies in our review because of heterogeneous study components and the lack of a common base case among study interventions, which complicate the comparison of studies and the ability to draw definitive conclusions. The heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis; rather, we performed a narrative synthesis and quality assessment. This approach is consistent with previous studies, and in practice, economic evaluations addressing a particular question do not generally present sufficient detail to permit adjustments required for a meta-analysis (40). Additionally, critical appraisal of the quality and reporting of health economic studies also vary. Because no minimum methodologic criteria or scoring systems exist, our evaluation of study quality was subjective.

Our review demonstrates that although smoking is an important public health issue, few economic evaluations of community-based tobacco dependence treatment programs in the United States have been conducted. However, the cost-effectiveness estimates found in our review are a fraction of the generally accepted cost-effectiveness threshold of $50,000-per-QALY. Given the degree to which tobacco influences numerous health outcomes and productivity, when the results are extrapolated to future savings, the low cost per quit or ICER is evidence that community-based cessation interventions are of great value and good investments for health.

Community-based agencies face challenges as a result of lack of tobacco control funding. At the time of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), many states established tobacco control programs; however, in 2018 only $721.6 million (<3%) of the $27.5 billion collected from MSA payments and state tax revenue in the United States was spent on smoking cessation and adolescent prevention (41). The median CDC-recommended level of state funding in 2014 was $48 million (7). In 2018, only 1 state (Alaska) funded its tobacco control programs at the CDC-recommended level (41). The funding for state tobacco prevention and cessation in 2019 ranges from 2% to 98.1%, with a median of 19.3% (41). The American Lung Association reports that the median amount states invest in quitlines is $2.21 per smoker in the state (41). Funding for community-based programs is inadequate, and such limited support will continue to exacerbate smoking-related health care costs and disparities.

Our review revealed a lack of focus on economic evaluation of community-based tobacco dependence treatment programs in the United States. We demonstrated these programs are cost-effective. It is vital to expand this literature given the effect of tobacco on health and costs. To improve the state of the science and understanding of results, as well as identify potential opportunities for uptake of interventions, such studies should be conducted. Future studies should adhere to and explicitly address key components of Drummond and Jefferson’s economic evaluation guidelines. Adding consistent base cases and valuation, subgroup analyses, cost-utility analyses, and standardizing approaches, especially related to measurement (eg, abstinence and costs) will improve comparability between studies and expand use in policy decisions. Future tobacco control economic evaluation research should also examine populations and areas with a high prevalence of smoking (eg, low-resource groups), in-person counseling, and mobile interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no funding mechanisms to report. The authors thank Fern Cheek, AMLS, AHIP, Associate Professor and Research Librarian, for her assistance with the development of the search strategy. Further details on the search strategy and definitions of terms, including a list of references, used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. No copyrighted materials were used in the preparation of this article.

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Sarah A. Reisinger, MPH, MCHES, TTS, 420 W 12th Ave, Ste 390, Columbus, OH 43210. Telephone: 614-366-4542. Email: sarah.reisinger@osumc.edu.

Author Affiliations: 1Division of Health Behavior and Health Promotion, College of Public Health, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 2Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 3Division of Health Services Management and Policy, College of Public Health, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 4Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, College of Medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 5Division of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/. Accessed February 26, 2014.

- Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, Simpson SA, Pechacek TF. Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. Am J Prev Med 2015;48(3):326–33. CrossRef PubMed

- World Health Organization. Quitting tobacco. Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI). https://www.who.int/tobacco/quitting/summary_data/en/. 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

- Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Heath J. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36(4):358–65. CrossRef PubMed

- Lando HA. Lay facilitators as effective smoking cessation counselors. Addict Behav 1987;12(1):69–72. CrossRef PubMed

- Lacey L, Tukes S, Manfredi C, Warnecke RB. Use of lay health educators for smoking cessation in a hard-to-reach urban community. J Community Health 1991;16(5):269–82. CrossRef PubMed

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs — 2014. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2019.

- US National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. Tobacco control monograph 21: the economics of tobacco control. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2016. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/21/docs/m21_complete.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2017.

- McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, Burdine JN, Sumaya CV. Community-based interventions. Am J Public Health 2003;93(4):529–33. CrossRef PubMed

- Drummond MF, Jefferson TO; The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ 1996;313(7052):275–83. CrossRef PubMed

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20(1):37–46. CrossRef

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22(3):276–82. CrossRef PubMed

- Burns EK, Hood NE, Goforth E, Levinson AH. Randomised trial of two nicotine patch protocols distributed through a state quitline. Tob Control 2016;25(2):218–23. CrossRef PubMed

- Graham AL, Chang Y, Fang Y, Cobb NK, Tinkelman DS, Niaura RS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of internet and telephone treatment for smoking cessation: an economic evaluation of The iQUITT Study. Tob Control 2013;22(6):e11. CrossRef PubMed

- Smith SS, Keller PA, Kobinsky KH, Baker TB, Fraser DL, Bush T, et al. Enhancing tobacco quitline effectiveness: identifying a superior pharmacotherapy adjuvant. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15(3):718–28. CrossRef PubMed

- McAfee TA, Bush T, Deprey TM, Mahoney LD, Zbikowski SM, Fellows JL, et al. Nicotine patches and uninsured quitline callers. A randomized trial of two versus eight weeks. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(2):103–10. CrossRef PubMed

- McAlister AL, Rabius V, Geiger A, Glynn TJ, Huang P, Todd R. Telephone assistance for smoking cessation: one year cost effectiveness estimations. Tob Control 2004;13(1):85–6. CrossRef PubMed

- Krupski L, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Mahoney MC, Toll BA, Carpenter MJ, et al. Cost and effectiveness of combination nicotine replacement therapy among heavy smokers contacting a quitline. J Smok Cessat 2016;11(1):50–9. CrossRef

- Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Heitjan DF, Shields AE, Asch DA, et al. Effectiveness of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(3):144–51. CrossRef PubMed

- Brandon TH, Simmons VN, Sutton SK, Unrod M, Harrell PT, Meade CD, et al. Extended self-help for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(1):54–62. CrossRef PubMed

- Davis AL, Faust R, Ordentlich M. Self-help smoking cessation and maintenance programs: a comparative study with 12-month follow-up by the American Lung Association. Am J Public Health 1984;74(11):1212–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) — explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013;16(2):231–50. CrossRef PubMed

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker T, Bailey W. Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, Hasselblad V, Baker T. Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation. JAMA 1997;278(21):1759–66.

- Kaper J, Wagena EJ, Severens JL, Van Schayck CP. Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD004305. CrossRef PubMed

- Feenstra TL, Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Hoogenveen RT, Rutten-van Mölken MP. Cost-effectiveness of face-to-face smoking cessation interventions: a dynamic modeling study. Value Health 2005;8(3):178–90. CrossRef PubMed

- Halpin HA, McMenamin SB, Rideout J, Boyce-Smith G. The costs and effectiveness of different benefit designs for treating tobacco dependence: results from a randomized trial. Inquiry 2006;43(1):54–65. CrossRef PubMed

- Fung PR, Snape-Jenkinson SL, Godfrey MT, Love KW, Zimmerman PV, Yang IA, et al. Effectiveness of hospital-based smoking cessation. Chest 2005;128(1):216–23. CrossRef PubMed

- Lennox AS, Osman LM, Reiter E, Robertson R, Friend J, McCann I, et al. Cost effectiveness of computer tailored and non-tailored smoking cessation letters in general practice: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001;322(7299):1396. CrossRef PubMed

- Eddy D. David Eddy ranks the tests. Harv Health Lett 1992;17(9):10–1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs — 2007. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/fda/fda/BestPractices_Complete.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2013.

- Institute of Medicine. Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2007. http://nap.edu/11795. Accessed April 21, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000.

- Bock BC, Hudmon KS, Christian J, Graham AL, Bock FR. A tailored intervention to support pharmacy-based counseling for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12(3):217–25. CrossRef PubMed

- Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav 2003;30(2):133–46. CrossRef PubMed

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull 2007;133(4):673–93. CrossRef PubMed

- Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med 1999;21(4):276–83. CrossRef PubMed

- Kangovi S, Grande D, Trinh-Shevrin C. From rhetoric to reality — community health workers in post-reform U.S. health care. N Engl J Med 2015;372(24):2277–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. Updated March 2011. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. http://www.york.ac.uk/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/SysRev3.htm. 2009. Accessed August 19, 2017.

- American Lung Association Editorial Staff. 20th Anniversary of Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. American Lung Association. https://www.lung.org/about-us/blog/2018/11/anniversary-of-tobacco-msa.html. Published November 20, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario